Notes on the Production & Special Thanks

制作コメントと謝辞

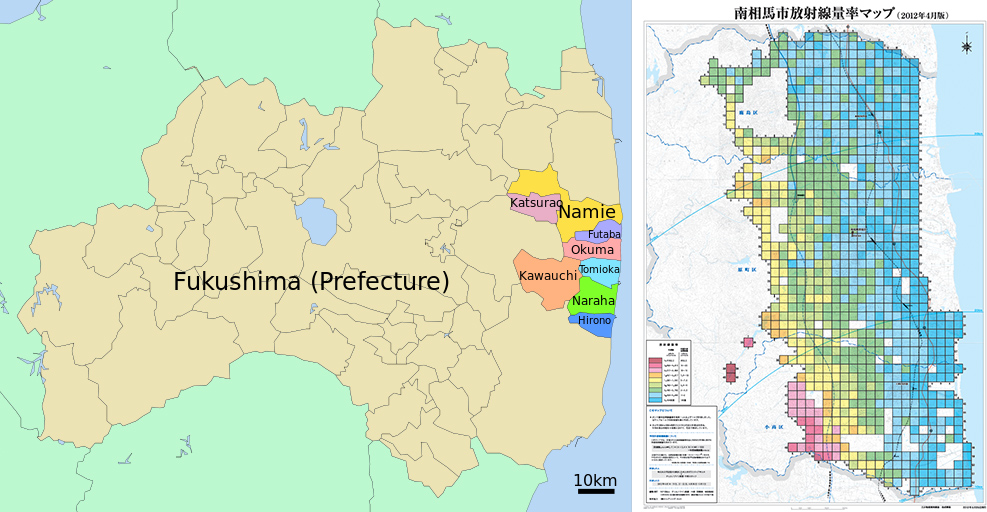

A central thing that kept this project going was my belief that the people of Fukushima deserved better than the momentary media coverage they received following the disaster.

To make this project I hitch hiked through the destruction, slept on countless couches and was aided by so many generous volunteers who helped translate so that Fukushima’s voice can be heard outside of Japan.

I am tremendously grateful for POV’s support which helped fund the coding of The Invisible Season. Thank you Adnaan for sticking with us from the beginning.

This project was made over a half decade on the thinnest of independent budgets. Trips 3 and 4 were crucial to the project and were in large part funded by the generous donations from all of you who contributed through Kickstarter.

僕の中でプロジェクトを進める動機の中心だったのは、福島の人々のことを、災害後の一時的なメディアの報道だけで終わらせるべきではないという信念だ。

『忘れられた季節』ウェブサイトのコーディングを支援提供していただいたPOVには大いに感謝している。初期から支えてくれたアンダーンにお礼を述べたい

このプロジェクトは5年間個人的な資金で制作されてきた。3,4回目の訪問なしではプロジェクトが完成せず、Kickstarterの寄付を通じてご支援いただいた方全てにお礼を申し上げます。ジェームズ、アンナ、僕に希望の扉を開いてくれて、そしてお礼に君たちの台所で手料理をふるまわせてくれてありがとう。また是非ディナーに招待します。

James and Anna, thank you for opening your doors to me and letting me use your kitchen for the Kickstarter rewards….you have another good dinner coming.

Yukari Naganuma, you are the foundation from which all of these stories and friendships became possible to share.

Jamie and Emanuelle, your always big thoughts, larger hearts and open doors both helped me on this journey and kept me going over this past half decade.

Thank you Hiroki Kobayashi and Yutaro Yamaguchi for your help on the road and making sure that we had all we needed to get into the Exclusion Zone.

Thank you Ayako Otoshi, Masayuki Sono, Yuri Yamamoto, Yutaro Yamaguchi and Naoko Yamazaki helping bring these words to the world.

長沼 由香里さん、すべての話と友情がこうして共有できるようになったのはすべてあなたのおかげです。

小林裕季さん、山口雄太郎さん、道中助けてくださり、そして避難区域に入れるように手はずを整えてくださってありがとうございました。

翻訳も何時間も手伝っていただいた。大年綾子、曽野正之さん、山本ユリさん、山崎尚子さん、これらの言葉を世に送り出してくれてありがとう。また、タケウチサトミさんには特にこの文章の翻訳を含め、ポストプロダクションの間を通して多大な助けをいただいた。

曽野正之さん、オスタップ・ルダケヴィチさん、松下朋子さんには夜遅くまで幾度とな

…And especially to Satomi Takeuchi who is translating these words here and has been such a tremendous help throughout the post production.

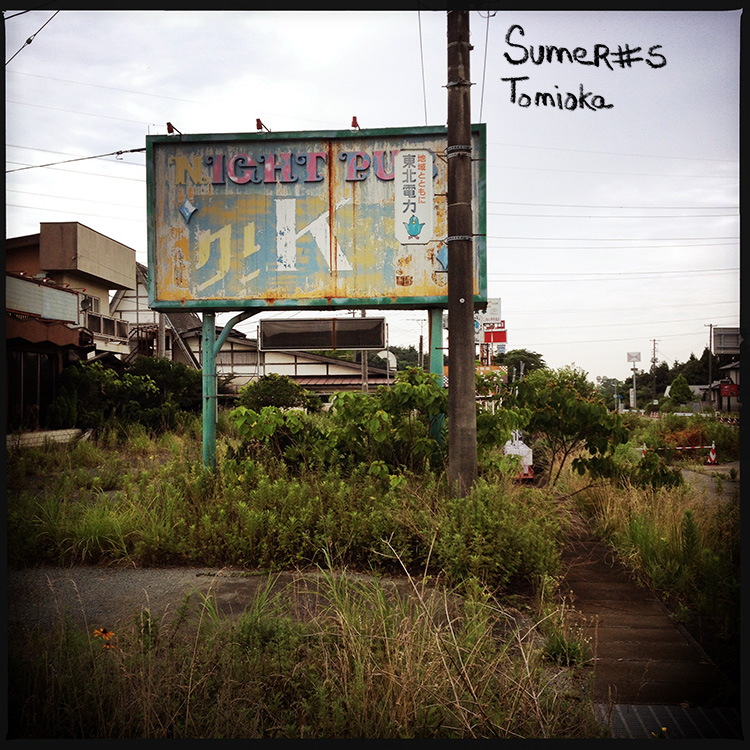

Masayuki Sono, Ostap Rudakevych and Tomoko Matsushita put in countless late hours to bring this project to life in the physical world for The 52nd New York Film Festival exhibit at Lincoln Center and Filmgate Miami where visitors could literally immerse themselves into the content, a groundbreaking first.

Lastly, none of you would be seeing anything here at all if it was not for Art Director Visakh Menon’s enduring and tireless commitment to this project. Created over a half decade on numerous continents while juggling all that life threw at him, he stuck with it to help tell these essential stories of our collective humanity.

Jake Price, Director

く付き合っていただき、リンカーンセンターでの第52回ニューヨークフィルムフェスティバルとフィルムゲート・マイアミに、ビジターが文字通り作品にもぐりこめるような展示を出品することができた。まさに画期的だった。

最後に、アートディレクターであるヴィサク・メノンの辛抱強く献身がなかったら、この作品は全く日の目を見ることがなかっただろう。5年も世界各地を飛び回り、彼自身にも色々とありながら、継続的にこの私たち人間のかけがえのないストーリーを作り上げてくれた。

監督 ジェイク・プライス

(翻訳:竹内さとみ)